Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

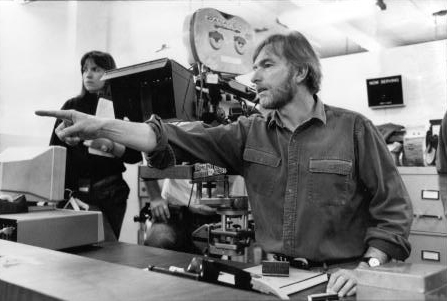

Peter Weir

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

OTHER HORROR PAGES

Some people, some artists, singlehandedly change the landscape in which they work.

Some fragment of the global perception of Australia, especially in the 70s, was bound up in the film Picnic at Hanging Rock. The Cars That Ate Paris and The Last Wave draw a unique horror out of their respectively country and city settings. Then there is The Plumber, as well as Gallipoli and The Year of Living Dangerously. Have you spotted the connecting thread? Add some international hits, Witness, The Mosquito Coast, Dead Poets Society and The Truman Show. We are talking, of course, about Peter Weir. At the time of this interview, in 1994, Mr Weir had just completed Fearless. In Sydney on a demanding promotional schedule, he graciously gave us some of his time to discuss this amazing body of work, and share with us one or two --

Weir'd Tales

An interview with Peter Weir

by Kyla Ward

First Appeared in Tabula Rasa#2, 1994

Tabula Rasa: So, the inevitable opening question: how did you start your work in film? What was your background?

Peter Weir: Yeah, I filmed around -- I first filmed not far from here actually [Kings Cross], in 1967. It was a short comedy I made while I was working at Channel Seven as a stage hand. And I made it for the Christmas Review, which I also staged and directed. They had a social club, and it did the kind of raffle, so I said well, let's do something...

TR: In keeping?

PW: Yeah, here we all are working on other people's programs, let's do it ourselves. Before that? Well, I had a fairly unsuccessful student-type background; you know dropping out of Uni, not very good at school, average to below-average student. I went to Europe for a year and a half, and came back determined to do something in the entertainment area, and got the stage hand job. I was always doing something at night, or on the weekend, writing, acting, directing. It was a wonderful time, the atmosphere of the late sixties, a wonderful time to be in Sydney. Which I think has only been equalled by the current period from what I can tell. It was a period where you felt you could do anything, and that was part of the international Western scene amongst young people, all the clichés were being born and it was very exciting. It was observable in my amateur theatrics that I had a better feeling for directing than for acting, and writing; I mean writing was something I did because there was no one else to do it. And since you were using friends there was no money involved, nothing would happen if you didn't have a a script. From there I went to Film Australia which was then called the Commonwealth Film Unit, directing various things, and I was just lucky, because all the grants had started. The generation ahead had said, look, there are a lot of young people doing things, we should have a fund, we should have a film school etc.

TR: And lo and behold, someone listened.

PW: Yes.

TR: You made your first feature in 1973, The Cars That Ate Paris...

PW: Well, you should really include Homesdale, have you ever seen that?

TR: I'll confess not.

PW: Well, you wouldn't. Occasionally it's in odd video shops, but it really belongs in that bracket. It's an hour-long, black and white film, that I shot in a house I was living in at the time. And it has something of the same, it definitely belongs with Cars, as Picnic does with The Last Wave. Sometimes it seems to take two films to work through a theme, or an idea.

Photo by Francois Duhamel. ©Lam Ping Limited. All Rights Reserved

TR: Well, you'll have to fill in the detail about Homesdale...

PW: It was the name of a guest house on a remote island, and they only took single people, for the weekend. It's about one of those weekends, it begins with the guests arriving, and they don't know each other. They've been carefully screened by the management, and really, the management provides a kind of Luna Park of events for the weekends -- unexpected events. The people who come tend to be very staid people, lonely, rather neurotic. So certain things happen which they put on, as part of the entertainment... they have studied the particulars of an individual, and will provide things relevant to that person. A series of games, some of them rather cruel. You gather the others have been there before, except for one, new guest, who's not played the game before. A Mr Malfery. He's related I think to the character in The Cars That Ate Paris, the little Mr Waldo; he's the little man, the little worm that turns. Over the weekend, he's always lagging behind and failing, not joining in really, and the denouement is that he takes their games very seriously, and he commits a murder. You begin to get on to what they're doing when you see one man go into the shower. He pulls the shower curtain and turns on the water... and the music from Psycho is in the background, and the shadow is on the shower-curtain and the knife, and the stabbing and screams; then you see him come out dressed, to the drinks before dinner, and he says to one of the other guests, 'have you tried the shower?'

The Cars That Ate Paris was something I wrote in London when I went with my wife for six months on a study grant, in 1971. I was attached to Elstree and Pinewood Studios to observe aspects of feature film-making. Funnily enough I met Hitchcock there -- he was shooting, I think it was his second-last film, Frenzy, and I got onto the set with one of these letters I had saying I was a student etc, and asked to meet him. And the First AD said 'oh look, he's very busy, everyone wants to meet him, I don't think he'll have time.' And at the end of the second day, he said 'I'm sorry mate, you know, bad luck.' Everyone was going home. I knew Hitchcock was still in his caravan, which was on the sound stage behind the flats which backed up to the walls, with just a Hitchcock width to walk around behind them. So I thought, well, you only live once, go round and confront him. So as I was walking around, I was thinking what to say to him, and I was looking down, and crashed into him.

TR: Oh no...

PW: And he was, startled! Didn't recognise me, and instead of saying what I should have said, which was 'I'm the Australian student, and I admire your films so much, I just wanted to shake your hand' -- that was what I should have said; but oh no no, I had to much more clever than that, and say, 'Do you know the shower scene in Psycho?' He just stared at me, and nodded, and I said 'Well I used the shower scene, not literally, no I didn't steal it, but in this film, I had it'; and it all came out like spaghetti, and I'll always remember, he just said to me 'Never mind. Why don't you come back tomorrow?' Which was very kind of him.

In that six-month period in London, a very creative period, I wrote three short stories -- the outline for The Cars That Ate Paris, based on an incident which had happened in France on the way to London. And then the treatment for The Last Wave and The Plumber, which I later filmed for television. So I had those three stories in mind when I came back to Australia.

TR: These four films do tend to be grouped, particularly in the minds of people studying Australian film into what suffices as the supernatural, of the horrific, perhaps even the mythic genre in Australian cinema. In these early films, instead of creating the basic story of the mystery-thriller or romance, you seem somehow to be creating an atmosphere, an idea of an Australian mythology. Which is interesting, because we're not supposed to have one. You create the idea of the isolated country town, which seems to exist in America, very strongly. And there's Picnic at Hanging Rock of course.

PW: Well, I'm sure there's many influences there, and some of them very obvious, some of them just personal. Growing up, I loved horror movies, particularly Hammer horror films. I loved anything to do with secrets, or mysteries, the unknown, the unmeasurable. And I think when I walked out of a cinema even at a young age; I'm now mythologising my own past!; but it seems to me, in the movie of my past, that what was outside was so plain, in the fifties, growing up then, so controlled, so nice and ordinary; and I took part in it like any kid, but I want to say I thought, 'This can't be all there is!' And as I got into the teen years it became stifling, claustrophobic. To the point where I looked forward to leaving, to going back to Europe. I mean 'back' because it was so recent really, three generations in my own case, it's the blink of an eye. So I was always interested in mysteries and stories, what you couldn't see. Like my Uncle Jack who'd been in World War II, and was the most interesting of my relatives really. We were pretty much ordinary folk, and didn't have much of a story to tell. No one knew about our past or who we were, except we had been Scots people. So there wasn't much to get there, I was always asking about where we came from and no one remembered. So I used to latch onto Uncle Jack, he was a bachelor uncle who'd come to dinner once a week and I was always pinning him down about the war because it seemed a starting point. I'd saved up my major question until I got deep into his war stories, which were often to do with humorous incidents, but I really was waiting to ask him, what I finally did, had he personally killed a Japanese? Because I'd imagined there must be some story there, that would explain Uncle Jack, and would be very interesting! And unfortunately, for me that young boy, he said 'No, I didn't, you never knew who you hit,' and all of that. So I kind of ran out of any possibility that he would have an interesting story.

TR: Still, people's identities are created with stories.

PW: Yeah. I used to love rummaging in peoples garages: garages were a most interesting thing in the fifties because there you could find things, artefacts, hidden things, you know, weapons and things, things people had brought back from the war. Here in this beautiful city with it's sparkling waters, a new merchant class were settling into these houses in the Eastern suburbs, like my father, looking to a prosperity that they'd never known, educating their children as they'd not been educated; everything was fine and dandy. But in these garages you could find things that people didn't want to talk about, and they were generally to do with the war; a gas mask, some medals, a strange piece of twisted metal. And weapons; there was a guy over the road who had a sub-machine gun in his garage, that he'd taken off a German officer and brought back. And then under houses, I always liked under the house, in the dark there, old things thrown out, photographs of people who had died under certain circumstances, things people didn't want to talk about. Just as your parents had cupboards in the bedrooms, drawers we were not allowed to open; but you did when they were out, and in one draw was your father's Masonic apron, and in another, your mother's drawer, were mysterious rubber tubes, things that were to do with sex and so on, which you didn't really want to know about and you closed that drawer pretty quickly. And photographs of men in uniform, which you could ask about but when you asked your mother about that young man in that airforce uniform her eyes misted over, and she said, "Ah. He was a war hero and he was killed in a Sunderland in the British Channel," and there's a hint of a love that never came to be. So this was really my other world. I was just one of those kids that was always dreaming; and it was wonderful to grow up pre-television, because, you know there's no question to me that the imagination develops in a different way, you're constantly making mental pictures. And comics were great -- they are really story boards. And you'll find that common experience with my generation in America, with the Scorseses, Spielbergs, Lucases and so on. It's a shared kind of popular culture which of course was fundamentally American on the one hand. and to do with World War II on the other. Look at Spielberg's Schindler's List, I mean, despite it's heavy story-

TR: And Empire of the Sun.

PW: Empire of the Sun, it's full of boyhood thrills, and even his re-creation of the Nazis in Schindler's List is influenced by old movies, comics even.

TR: Was there anything that attracted you or interested you about the Aboriginal stories that you picked up on in Last Wave?

PW: Well, you know, I don't really think I ever thought about the Aborigines, growing up. Not like today. The only time I ever thought about them, as I recall, was seeing Jedda, which had an enormous impact on me, the first Australian film I'd ever seen. I saw it at Double Bay. There it was, in shocking colour, there were the colours of the Centre that I'd never really seen; the odd tourist brochures didn't mean anything to me, to me any thoughts of travel or adventure were to do with Europe. And that film also had a kind of erotic content, the stealing of the woman and her semi-nudity. It was profoundly mysterious and interesting, and overwhelming really, and seeing the film again if you can get past the first set-up of the story, which is very wooden, and get on the run with this couple -- have you seen it?

TR: I've seen segments, that's all I'm afraid.

PW: It's at it's best when there's little dialogue, a beautifully realised piece of work.

But otherwise, at school we were taught the way of that period, which was a stone-age culture which, it was said sadly, is virtually none-existent as a result of contact with Europeans, I mean that's about it.

TR: If you dig back in your mother's bookshelf, you find the previous generation of schoolbooks and histories-

PW: Australia was of no interest to me. None. I couldn't wait to leave, and I left at twenty. In a way I never came home. Came back married, and went on with my own life, and buried myself in sheer, pure creativity... The city was a giant studio for me.

TR: Can you talk about Picnic at Hanging Rock, the strangeness of the land. The people not quite fitting.

PW: Yeah, that's there. And in The Last Wave where the Aboriginal is coming to dinner. The Gulpilil character -- and he brings the old man with him--

TR: Remarkable scene, if you don't mind me saying.

PW: No, I'm delighted! I like the moment when the wife says, while they're nervously waiting, 'Here I am, a third-generation Australian and I've never met an Aborigine.' She's nervous; and it's one thing to see the young fellow at the door, but then, disturbing to see the older man. Why is he there?; and so on. He says 'This is Charlie', and the wife says 'well who is he, what's he doing here?'; She's so nervous, reflecting the reality that most Australians have no contact with Aboriginals.

TR: I distinctly remember reading a review of Witness, and they are describing the opening sequence, and saying 'You're in a Peter Weir image-scape', a landscape. It went on to describe you as a symbolic director, and I must confess that's one of the things I see throughout your work, even up to, or particularly, Fearless. You've been in America and for the American release, and what I've been hearing, particularly in the pre-Oscar diagnosis, is that a lot of people have found it, even before they get into the cinema, the basic idea, uncomfortable.

PW: Yeah.

TR: And I'm wondering what's the difference between seeing [the air disaster] presented in this cinematic way, and on the news?

PW: On television they're very highly-rated, whenever they do one of those re-constructions; in fact the very accident on which Fearless was based, which is the accident in 1989 in Sioux City, the DC10 -- they did that with Charlton Heston as the pilot, and emphasised the Rescue Services, interestingly.

TR: That makes it into a story of heroism--

PW: Yes. And they showed not one single shot of the passengers during the forty minutes the plane was in distress -- I was staggered. The story itself was really more interesting than they showed it, because they put in phoney tension between the fire chief and the ambulance chief -- you know that sort of stuff -- and in fact the locals complained and said there was no friction.

TR: Oh, but they just had to create a hero and a villain.

PW: When I was speaking to the survivors of the accident, they were very reluctant to talk because of that television programme, and said it was silly and people never get it right. So I said, well, tell me, and then I used their observations. The result was, for many, too real. I've noticed that even with acquaintances of mine, that they'll say, oh when's you're new film coming? I can now almost tell who won't be able to take it, so I'll say to them I don't think you should go. And why? They ask me, and I say, well, it's disturbing. Not that you'll see any blood and gore, but the ideas of the film do bring you to questions to do with mortality and how to live -- all the things that made me interested! And I'm invariably right because the person will say, oh thank you, I'm glad you mentioned -- oh, I couldn't take that at the moment. I just couldn't take anything like that right now. In travelling round the world with this movie, the interviews and so on, you do see that many people appear to be in good physical shape, jogging away, and going to the gym and so on, but are emotionally pasted together with chewing gum and wire. Anything that even opens the door to the most interesting questions of how to live or how to face the inevitable is something that they'd rather not think about, or at least, 'not at the moment'.

TR: Possibly what differs Fearless in the general mind to things like Schindler's List is that there is no moral that be drawn at the end.

PW: There's no conclusions, no polemic. And really the viewer finally makes the film, there is room, for you to join in, to allow your own unconscious to play with the film and become a part of it. I always thought the theatre setting was ideally suited to this film in the sense that the audience are passengers, and you take off!

TR: The central character that Jeff Bridges portrays. There's the intimacy created -- just in that scene where he's lying asleep and the camera moves in closer and closer to the ear, and the sound changes, and we realise he's dreaming -- he's reliving the crash -- and we're going down into the dark side with him. In a way it reminds me of Allie Fox, Harrison Ford's character in The Mosquito Coast.

PW: In a way there is a kinship.

TR: And I would say, that each one of them had their own demon.

PW: Both were truth-seekers. Compelled to speak the truth for different reasons; Allie all his life, and Max as a result of his singular experience. And those sort of people are very uncomfortable to be with. In both cases their families find it hard and struggle along with them. Allie suffered from the malaise of the materialist; he was unable to have another dimension in which to see things. In the case of Max in Fearless he has the potential, he's been opened up.

TR: Yet, a character suffering vertigo, a dreadful loss of all his ties.

PW: Yeah, the highwire walker that looks down and all of a sudden thinks, 'How do I know how to walk on this wire?' It's an odd film, Fearless, a film that I think yields more on a second viewing.

TR: Has the original novel, Rafael Yglesias' Fearless, been published?

PW: Yes. I guess they'll release it with the film.

TR: How would you say the two interrelate? You can make a general principle of it if you like, because you've worked with novels before.

PW: I'd rather work with an original screenplay. You can get lost very easily, adapting a book. The structure is so different, in both cases.

TR: Did you have any contact with Joan Lindsay, over Picnic at Hanging Rock?

PW: Oh yes, I had to be approved by her. On the way to visit her at Mulberry Hill, her farmhouse where she lived with her husband, the literary agent who had set up the meeting warned me not to ask her about the truth of the novel. Of course I knew I would. I wanted to get it out of the way fairly early. I said, looking at the literary agent, 'Forgive me', turned to her and said, 'I'm not supposed to ask this, but is it true?' She looked very tense and looked at the agent as if 'didn't you tell him?'; then said, 'I really don't want to discuss that, please don't ask me again.' She appeared one day during the shooting, and I kept my distance from her because I could hear her voice drifting over -- she was a charming woman by the way -- but I could hear her saying, 'Oh, but I didn't imagine him looking anything like that'. And then I saw her after the film had come out and she was besieged by the press, and she said to me, 'Oh, the press keep asking me about the truth of the matter and I don't know what to do. I don't know whether I should tell them or not.' And I said, keep your secret. It was never of interest to me whether it had happened literally or not. Fairly clearly it hadn't happened literally, otherwise there would have been some mention in the newspapers of the day, a scandal like that! It was a metaphor of some kind, for Joan Lindsay. People disappear. And what is it to be 'disappeared'?; to be neither alive nor dead. Why is it so important to bury people, why do we need to see their bodies? It led me to do research in that area, particularly the great numbers of grieving people, widows and mothers after the first World War, whose sons and lovers and husbands disappeared, in enormous explosions. Possibly they were in a hospital with a loss of memory, which was written about -- shell-shocked, and they may wake up one day and say who they are. And they lived in this twilight between life and death. So that was enough of a mystery for me.

TR: Mysteries aren't necessarily there to be solved.

PW: That was the power of the piece. And the only country that couldn't take the film was America. We could not get a release. Distributor after distributor looked at it, complimented the technical side of it, and said-

TR and PW: 'But it doesn't end!'

PW: Yes! One distributor threw his coffee cup at the screen at the end of it, because he'd wasted two hours of his life -- a mystery without a solution!

TR: So, perhaps on that note, without a proper ending!; Mr Weir, it's been a pleasure talking to you. Thank you for your time.

©2020 Go to top