Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

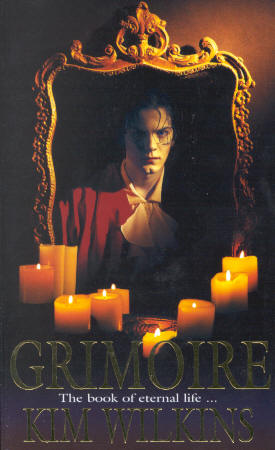

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

OTHER HORROR PAGES

Grimoire

by Kim Wilkins, Arrow, 1999

Reviewed by Kyla Lee Ward

"...if we destroyed it, then one day decided that we needed it, discovered that there was a way we could work around the danger and succeed, we'd never forgive ourselves."Holly laughed a bitter laugh. "None of us can forgive ourselves anyway."

Holly Beck should never have returned to her home town in rural Queensland. Despite family pressure and her own guilty conscience, she should not have gone through with the marriage to her childhood sweetheart. Now she has escaped–back to the city and the academic world she craves. But more than the founder's collection of rare books ended up in Humberstone College, and the price of this liberation may prove more than she was expecting.

Holly Beck should never have returned to her home town in rural Queensland. Despite family pressure and her own guilty conscience, she should not have gone through with the marriage to her childhood sweetheart. Now she has escaped–back to the city and the academic world she craves. But more than the founder's collection of rare books ended up in Humberstone College, and the price of this liberation may prove more than she was expecting.

Kim Wilkin's second novel, after 1997's The Infernal, is a refinement of her themes of secret history and contemporary damage, and a superior use of her Australian setting. Conveyed through three main story lines, each comprised of multiple points of view, this is a dense and complex story that only manages to integrate itself during the last few beats. The lengthy flashbacks to Victorian London may burden the whole, but result in a fascinating evocation of demonology and the processes of black magic.

To traffic with demons, in the classical tradition, is to play a dangerous game. The demon's sole interest is the damnation of the summoner's soul: it grants power only a means to this end. Damnation is an unfashionable concept these days but Holly and her fellow students–Justin and Prudence–are all close to crossing some kind of line, if only in their own estimation. Justin blames himself for the death of his mother. Prudence's loud mouth and promiscuity may seem laughable at first, but her petty revenges against her family are escalating. And then there are the professionals, members of the coven that has formed around the fragmented grimoire of Victorian magus Peter Owling. It is only when Holly encounters Christian, a victim of Owling's original attempt to grasp immortality, that any of them stand a chance of surviving.

Haunted mirrors, subterranean labyrinths, gatherings of robed ritualists–this is romping high gothic with sex oozing out of every moist crevice. Much of it is regrettable–Prudence's habits are, after all, a kind of self-abuse–but Wilkins also pulls off the interesting trick of victimising male characters through their sexuality. The scene where Justin is basically prostituted for information is as cringe-inducing as anything involving a woman. But even when describing worse horrors, Wilkin's style is delightfully readable–she has a gift for offering up the right detail to conjure a scene–and her commitment to her characters is absolute. In the midst of all the crimson silk and poisoned wine, I found a genuine sense of pathos for the detritus of history, the poor and vulnerable whose lives do not make the official record. Whose deaths may be believed by those with power to hold no significance.

It is an interesting quirk of horror that the presence of demons is seldom extrapolated to angels. Although Wilkins does address this in 2001's Angel of Ruin, the way that word is applied herein quavers along the edge of blasphemy. The remedies of cross and holy water are not applicable and this is only in keeping.

In this interview with Tabula Rasa, Kim Wilkins speaks of her dissatisfaction with genre labels, for among other reasons, their reduction of the complexities of work such as this. "There's such a strong feminine element, and often a strong historical element, and horror as a term isn't elastic enough to cope with those extra elements". In keeping with this philosophy, Grimoire offers no pat resolution. Although the climax is thoroughly earned, redemption, from past sins or demonic pact, does not come easily. Love and trust may be the key, but this is hard enough for saints, let alone those mired in all the pettiness and complexity of everyday life. Why not chose power, the volume whispers, why not sacrifice everything for the prospect of eternal life? What, truly, do you have to lose?

©2020 Go to top