Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

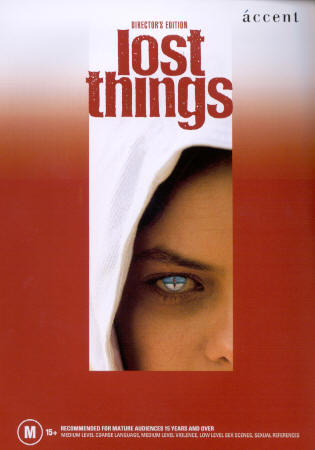

Martin Murphy & Ian Iveson

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

OTHER HORROR PAGES

Edgy & Experimental & Weird

A Conversation with Martin Murphy and Ian Iveson

by Dave Hoskin, 2004

- This article was first published in Metro Magazine.

The café is packed with people, but finding Martin Murphy is a lot easier than you'd think. It's a sunny day in Melbourne, and the city centre is full of people out enjoying Cup Day. However, only one of them is still wearing a suit in the surprisingly balmy weather, the same suit that he'd worn at the Lost Things screening the previous night. I walk up unerringly and introduce myself, to the slight surprise of the film's producer Ian Iveson. He smiles when I explain exactly how Martin stands out from the crowd.

The café is packed with people, but finding Martin Murphy is a lot easier than you'd think. It's a sunny day in Melbourne, and the city centre is full of people out enjoying Cup Day. However, only one of them is still wearing a suit in the surprisingly balmy weather, the same suit that he'd worn at the Lost Things screening the previous night. I walk up unerringly and introduce myself, to the slight surprise of the film's producer Ian Iveson. He smiles when I explain exactly how Martin stands out from the crowd.

Our conversation is easy-going, and both men share a dry sense of humour. Lost Things was not an easy film to make, but they repeatedly emphasise just how important it was for them to be pursuing their craft. Both have worked in the industry for years, but at last night's Q and A, Martin had commented that they didn't want to spend the best years of their lives trapped in development. I ask if this is how it had felt trying to get Lost Things off the ground? They shake their heads.

'Not Lost Things,' says Ian. 'Lost Things was the response to feeling like life was slipping past.'

'Lost Things was liberating for us,' Martin agrees. 'Because we took control and we were out there suddenly, being the film-makers that we wanted to be.'

'If we hadn't been able to find the small amount of seed money we needed to go and shoot,' continues Ian, 'we would have shot on DV and we would've shot with five crew. As it happened we just happened to get some good cast and good crew together and the money to go, "OK, we'll go Super 16". But if it had to be done with five grand, we would have done it for five grand...

'The really interesting thing was working on a project that you knew would be made. Because when you work in development... I've developed various projects; some have got very close; some haven't got very close. But there's that feeling that, you know, the AFC, where they give the script development for a film, there's a one-in-ten chance that it'll go on to get made.'

Did you approach the AFC for assistance?

Ian nods. 'We did. We'd already shot it. We'd cut it and we showed it to Duncan Thompson... he was a project officer at the AFC at the time and he really enjoyed it, even at rough-cut stage... Unfortunately he said you've got to put this in for production development, and then promptly left. And in came an arthouse director who'd made a couple of arthouse films and just hated it... He said, "All of these children are awful. All of these kids—they're just horrible."'

Martin shakes his head in disbelief. '"They're not normal." They were asking us why we hadn't taken a commercial approach. They wanted to know why we weren't using...' Sarah Michelle Gellar? 'Yeah. And I said we wanted them to look like the people who were watching the movie—just normal people. We didn't want them to look like they'd walked off a catwalk into our movie. We wanted them to look like people that you knew so that you could relate to the film, so you'd be sucked into the story, so you'd buy it and you'd be more scared. And they didn't get that at all... whereas Showtime did. And they surprised me.' So the AFC thought it wasn't commercial enough and Showtime thought it was fine? 'They loved that it was edgy and experimental and weird. They loved that, and they said don't lose that in your final cut; don't lose what you've got now. I was so taken aback by that, and it was such a shot in the arm for us. It really gave us a lot of momentum to keep going with that support from a big company like Showtime.'

I remind Martin that at the Q and A after the screening he had said, 'genre doesn't fit the program' at film festivals. What did he mean by that remark?

'Well it just seems that genre films aren't readily welcomed by the programmers at festivals. I expected we would have had a better look-in than what we did—I mean we had no festivals. Genre films do play at festivals occasionally, but generally my experience has been that mostly they're a forum for "straight" drama.' He pauses to consider. 'I guess it's because the festival is an adult film-going public's event, and horror films are primarily aimed at a young audience because there is something anarchic about the genre. They present ugly moral questions, uncomfortable moral questions. They play with taboos; they break open conventions, [they're anarchic because] they break down societal structures and expectations to create the horror. So I suppose because it talks most directly to a younger audience then festival programming really isn't aimed at that younger audience, and so genre films don't really feature.'

One of the distinctive things about Lost Things is the decision to set a horror film on a bright sunny beach. Ian confirms that he came up with the kernel of the idea. 'When you're looking at genre... I remember talking to Mark Ordesky who was at New Line... and he said, "We're like everyone else. What we want is genre with a twist." [...] And that's what we're looking for, we were looking to try and take a genre and subvert the conventions, and that's a dangerous path to take, it's a high risk that you can fuck it up.'

Were you worried about that?

'I didn't have any doubts at all,' Martin says, emphatically. 'I knew we could make it work, absolutely. I had so many experiences growing up in the country where I've been somewhere on my own, and because you think that you see someone out of the corner of your eye, suddenly a peaceful paddock has a menace... The environment might be benign, and then you think there's someone else there at the campsite that you don't know. The stakes rise; there can be a shift. Sometimes it's just a cloud moving across and everything getting a bit darker and cooler, it just changes the mood of the environment. We couldn't do what mainstream horror films do. I think that the role of truly independent film is to offer an audience something that's entertaining, but also that's charting some new territory in some way. Because how else can we compete with the blockbuster?'

We move onto Lost Things' screenwriter Stephen Sewell. I mention that somehow I'd got the impression that he'd be a fairly tough collaborator. Martin smiles. 'It's funny, I've worked for Steve for about five years and I'd always heard people saying, "You're working with Steve...? How are you going? Are you OK?" And I'd say, "Yeah, he's great." And I said to him, "Steve, people talk to me like you're a serial killer." He's just been terrific. Steve is a very passionate artist, and, you know, he's got his opinion, you fight things out, you turn things over...'

'You want to work with passionate people,' continues Ian. 'So one of the differences about this film was the way in which we said OK: August the eighth—we're going to shoot on October 22nd. Steve disappears for two weeks, comes back, starts writing ten pages a day, which is quite unusual. Then we went through a series of very intense script meetings and read-throughs. It was a really collaborative approach to the writing, which normally you wouldn't get. Normally he would have much more time to write, he would then come back, do another draft spread over two, three, four years or whatever. This was condensed down into a much shorter period, so I think it made him more open. I think that he would admit that he is a reluctant rewriter...'

'He's stubborn.' Martin interjects.

'Stubborn as a mule,' nods Ian. 'In this, I think he knew that we were up to speed, and we were running down a hill, and the momentum was travelling over everything.'

How do you think he influenced the film? What did he bring to the table?

'Oh, he just brought the computer and the paper really.' Ian laughs. 'We had all the ideas. He just wrote down what we said.'

Martin attempts a more serious answer. 'Steve brings all the dense conceptualisation. I thought he was going to write a straight three-act, linear-progressing horror film. And he wrote something that was about fractured time and memory and it was so layered, it brings depth to the project, I think. That's why it was such an exciting piece to work on as a director, to get my head around this dense story, and its interweaving non-linear plot...'

'And also what was really interesting,' says Ian, 'was that... he was putting set-ups in without really knowing how to resolve them. He was feeling his way into the story and setting up stuff, some of which eventually got pulled out cos they never got resolved.'

'He's instinctive like that,' confirms Martin. 'He says that when he writes a spirit takes him over. He's been writing for so long, he doesn't do what I do which is a lot of note-taking and plotting, [...] a lot of time developing my ideas. Steve will have lots of conversations and then he goes into the tunnel, and he says this spirit overcomes him and he writes in this very instinctual way.'

Picking up on another of Martin's remark at the Q and A, he had mentioned that he preferred the term 'film-making community' rather than 'industry'. Why that term in particular? 'Because we're such a small industry,' he explains. 'I like the word community because I think that encourages people to think of their colleagues as allies. Not people to be competing with, but people that we can all share ideas and experiences with. We should be supporting each other. Like, colleagues of mine who are working in commercials donated film stock to this film. They were on a wage, I wasn't, they helped us out—that's a wonderful thing to do.'

Ian nods in agreement. 'And people like Robert Connolly who's been really generous in his advice. David Redmond and Nigel Odell from Instinct, they've been really generous too. And I guess we've passed that on. I've had three different film-making teams ring up since Popcorn Taxi last Wednesday in Sydney saying, "We're making this low-budget film and we'd really like to get together and talk and basically strip-mine your brain of any useful information."'

'Their success is our success.' Martin asserts. 'Because the more success we have, the more we'll get Australian audiences to come back and watch Australian movies. That's why I think we've got to help each other.'

'This very subject was the subject of a talk that David Puttnam gave when he was here about six years ago I guess,' Ian continues. 'He said what you have to avoid happening here in Australia, is what happened to us in England where we had lots of these little lifestyle companies turning over five to ten million pounds a year... You've got to forget all of that, you've got to get together and you've got to form strong, powerful alliances to go forward. Otherwise you'll just be a cottage industry; you'll just be lifestyle hobby film-makers.'

Mention of people's experiences in the industry, particularly those who have made horror films, reminds of how the Spierig brothers' film Undead (2003) had been well received in America but seemed to be shunned somewhat locally. 'There is an attitudinal thing,' Martin agrees. 'I find that if you're overseas, in Los Angeles or London... In Australia, I've made this film; the first question most Australians ask me is "Are you happy with it?" The first thing that you'll get in Los Angeles or London is, "Congratulations! That's fantastic you've made a movie." And I think that says it all—we expect failure here. I think that attitude sucks. That's why I think it's good for film-makers to go overseas for some time, or to do it on a semi-regular basis, to just be exposed to people who are can-do, who have that attitude.'

As a final reflection, I ask them individually what are they most proud of in the film?

'Personally I'm really proud that I've got the audience laughing and screaming in the same session at the cinema,' says Martin. 'I love the fact that they're taking in this story, they're following these characters, and they're laughing when the characters are behaving naturally or funny. And then they go all still. I've watched the audiences, they go still, they go really quiet, and some of them scream and some of them jump. You can see that you've got them—and I love that. That is so exciting to watch.'

Ian thinks for a moment. 'I guess that we took such a garage band approach to doing it, and it's going to go out on fourteen screens in Australia. We're just hopefully about to sign up an ancillary deal in the next couple of days. It's being shown in eleven overseas film festivals. We've sold fifteen territories I think, depending on what the next report says. That's not bad, it's being taken seriously.'

'People are seeing it,' emphasises Martin. 'It hasn't stayed on a shelf. It's just so exciting that the film is out there and it's playing in cinemas.'

©2020 Go to top