Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

Wake in Fright

OTHER HORROR PAGES

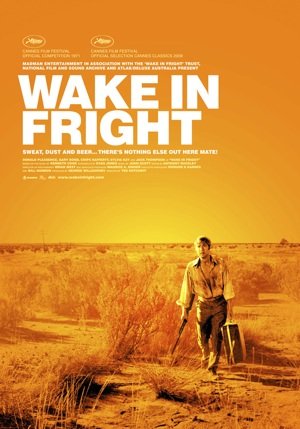

Wake In Fright

Directed by Ted Kotcheff, 1971

A review by Kyla Ward, 2009

'Doc' Tydon: All the little devils are very proud of Hell.

'Doc' Tydon: All the little devils are very proud of Hell.

When the Bundanyabba police chief enquires what John Grant does for a living, he answers he is a bondage slave of the Education Department. "A teacher," he qualifies, in response to the man's suspicious frown. Gary is travelling back to Sydney for the Christmas holidays, from a flyspec even further outback than Bundanyabba. He is only stopping here overnight. He's only come down to the pub for a cold drink and a bite to eat. This is his downfall, of course. When venturing into the Underworld, you must never eat or drink. Doing so means you will remain forever.

In the near-forty years between its initial release and the premiere of the restored 35 ml print at Cannes in 2009, Wake In Fright developed a fearful reputation. Adapted from the novel by Australian author Kenneth Cook, the film apparently sent people fleeing from cinemas in Sydney and Melbourne but scored its director a nomination for the Palm d'Or. It was credited with seeding the current Australian film industry, as well as starting the career of iconic actor Jack Thompson. It was suspected of being that phantasm, a genuinely Australian horror movie. But given the lack of watchable prints and any kind of home release, it was pretty hard to judge.

The lack of copies was due to the long absence of the negative. This was rediscovered in 2004 after a harrowing decade-long search by the original editor, Anthony Buckley, and restored by the Australian National Film and Sound Archive. Now that the DVD has made things easy, three questions confront the historian and casual viewer alike. Is it horror, is it Australian and is it really that good?

The opening 360° pan that starts at the railway station, ends at the railway station and goes absolutely nowhere in between, sets the scene. John Grant, with his English accent and white suit and tie is as familiar and friendly as this place is hostile, though at the start this is not overt. The train is uncomfortable, but fulfils its function. In Bundanyabba, the pale, antique buildings are decayed and out of place themselves amidst the red dust and blazing light, but not ugly. The welcome John receives, after his initial inspection, appears sincere, as complete strangers press drinks upon him and show him the town's secret corners. He is accepted without apparent demur into their primary ritual, betting on the toss of coins in a two-up school where plastered workers lose their week's earnings. "It's death to farm here, and worse than death in the mines," comments his only critic, "You want them to sing opera as well?" This is 'Doc' Tydon, whose lucidity conceals something rather worse. The roar of the crowd engulfs him, the darkness looms, the coins spin and flash. Soon enough, he is broke and naked in a hotel room, his flight gone and options dwindling.

What is this but an archetypical horror story? Think Lovecraft's "The Shadow Over Innsmouth" or Barker's "In the Hills, the Cities". If the inhabitants do not turn out to worship the Great Old Ones or to be part of some arcane gestalt (although a case could be made), the atmosphere does not suffer. Even during the intervals of daylight, John Grant is sucked inexorably towards deeper darkness. As said, this is a descent into the Underworld and the fact the second circle is a fragilely neat farmer's house only brings the horror home: another trait of the well-crafted genre tale.

His descent hits its apparent depth in the rightly notorious sequence of the kangaroo hunt. This is another ritual, an initiation by blood the like of which has been seldom put to celluloid. But it is followed by another initiation and a worse degradation. This is the true climax of the film, where John's manic hallucination of his last forty-eight hours (a vastly effective montage including the sight of 'Doc' with the two-up coins laid across his eyes) decodes what is taking place beneath its cover. The complete lack of acknowledgment, even in the aftermath of the event, somehow makes it worse.

But it is the following "epilogue" that I think makes Wake in Fright a genuine horror story. John's attempt to reclaim himself, to literally walk away from what he has seen and done, provides the knife twist. The eventual ending of the film has an upsetting ambiguity. Is this redemption or damnation, or is there no longer a difference?

Australia has isolated country towns like nowhere else except, apparently, Canada. At the 2009 Sydney Film Festival, director Kotcheff said that what drew him to Cook's story was its relevance to his native country. That in many respects a cold desert and a seal hunt would work equally well. The seal hunters would not be asking the newcomer whether he liked the 'Yabba and I have never heard of seals striking back with their razor-sharp claws (plaintive cry on behalf of our fragile native wildlife this is not!) But he may well be right. The fact remains the film was shot in New South Wales, more or less exactly where the book's author set it.

I mentioned previously that John Grant was familiar. Of course he is; the film positions him as such. But someone ticking off the Australian elements of the film would quite conceivably miss him. Kangeroos, flies, a Martian palette, a posh-sounding faggot in a white suit. But the foreigner out of place is a quintessentially Australian trope, and it works from either side. It's not hard to imagine how the "little devils" themselves would view the proceedings of Wake In Fright. Classic Australian comedies such as On Our Selection (Dir. Raymond Langford, 1932) are cut from uncomfortably similar cloth. The descent of this hero into the Underworld is framed by the distrust of the mob for the intelligentsia. Of course, it's pretty safe to say which side a film festival audience is on, along with anyone who invokes myths in a review.

So is this film Australian? I don't believe that ticking boxes, to say this percent of the crew, cast or funding, gets us anywhere in this case. It is a film with something to say about Australia and if this something has universal overtones, so much the better.

By this point it should be clear that I do think the film is good. Its strong visuals, startling performances and simple story combine into a truly powerful experience. It was never going to do much for Australia's image as a tourist destination, although it is rumoured to have prompted a reform of the system of indenturing inexperienced young teachers to rural postings. But the fact is that where John Grant really spent Christmas was in the chiaroscuro depths of his own psyche and at least one of the monsters he encountered was himself. Too many narratives, horror and otherwise, sell short this ordeal. The historian and the casual viewer may rest assured that neither they, nor the many people whose dedication has at last enabled us to view this work, are wasting their time.

- The original advertising

- External link: IMDB listing

©2020 Go to top