Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

OTHER HORROR PAGES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

by Rick Kennett

- This article was originally published in SF Commentary 78 in 2003.

Thinking back, I couldn't remember either the story title or its author.

Thinking back, I couldn't remember either the story title or its author.

In fact I had only the vaguest memory of having read it in one of those scaled-down-for-juniors Alfred Hitchcock anthologies borrowed from the school library, circa 1969, and had only the scratchiest recollection of what the story had been about. What I did remember -- vividly -- was the illustration: A man's face pressed against a window, peering in at a stone floor bulging up in two enormous lips.

This exact same first contact with an unremembered author with a forgotten story in a vaguely recalled book had already happened a few years earlier on the other side of the world. But it would be more than twenty years before I learned of it.

Move along a couple of years. I'm sitting my final English exams. The paper said to write about your hobby. So I wrote a little essay about ghost hunting. Not that I'd done any, but even at that tender age I'd been reading up on the subject, immersed in the books of British spook chaser Elliot O'Donnell who I first encountered with Screaming Skulls in a ship's library in the middle of the Pacific. So I waxed knowledgeable about dusting floors for footprints and trip wires and thermometers and recording devices and cameras ... and it occurred to me then that I was not only drawing upon O'Donnell, but also dredging up things read in that long ago story with the face at the window and the lips in the floor. Obviously it had had something to do with ghost hunting. But I still didn't remember its title or author. (I have sometimes wondered what the examiners made of my essay. At any rate I passed my English exams.)

Move alone to January 1975. I'm on my first ever holiday alone, flying off to Canberra to visit the War Memorial. Canberra is an oddity among the world's cities, purpose built as a national capital rather than developing from early settlements. Parked out in the middle of New South Wales and embedded within its own Australian Capital Territory, Canberra is like a country town with gigantism. And me ... I'm a total innocent abroad with no idea of the city's excellent bus system. Despite the heat of that Canberra summer I walk everywhere, equipped with fly repellent and map. I walk down broad avenues and broader main roads, I walk across half the city from my motel to the War Memorial, and around and around in circles because that's the way the city is. Then one morning, hot like all the others, I walk out of the motel and just strike out in a direction I'd not previously taken. Half an hour wandering suburban streets brings me to a small shopping centre. For no particular reason I stroll into a newsagent where my eye is caught by the lurid cover illustration of a Panther paperback: a wiry-haired child, sporting the thin legs and swollen belly of a starvation victim, is jogging through a red-lit landscape of cracked earth and stunted trees. Trotting behind him, connected by a length of chain, is a pig. The title reads Carnacki the Ghost-Finder and the author is William Hope Hodgson.

If the cover alone isn't enough to make me shell out the required $1.20, the clincher's the blurb quoting H. P. Lovecraft: "The work of William Hope Hodgson is of vast power in its suggestion of lurking worlds and beings behind the ordinary surface of life" ... at which point I actually look about the shop, wondering what was lurking beneath the surface of this particular bit of ordinary life.

William Hope Hodgson, I read on the flyleaf of the book, was born in 1877 in Essex, England. He ran away to sea at age thirteen and spent eight years in the Merchant Marine before settling down to a writing career. He produced several outstanding works of weird fantasy, and is perhaps best remembered for two novels, The House on the Borderland and The Night Land. He joined the Royal Artillery at the outbreak of the First World War and was killed in action in 1918.

Over the next couple of days I dip into the book, going from one promising title to another: "The Thing Invisible", "The Gateway of the Monster", "The House Among the Laurels", "The Haunted Jarvee", "The Whistling Room", "The Horse of the Invisible", "The Find", "The Searcher of the End House" ... I read the longest story, the novelette "The Hog" while waiting in Canberra Airport for the plane back to Melbourne, occasionally looking up as RAAF Hercules transports take off for Darwin, devastated the month before by Cyclone Tracey.

Hodgson tells his nine stories within a framing device. The narrator Dodgson and three others, having received "curt and quaintly worded" cards of invitation from Carnacki, forgather at their friend's home at 472 Cheyne Walk in the London suburb of Chelsea. There, after a "sensible little dinner" which is covered in the first page, if not the first paragraph (Hodgson worked in the Edwardian equivalent of the pulps and knew how to move a story along), they pull up their chairs to the fire, cigars and port are handed round, and Carnacki, puffing on his pipe, tells them about his latest ghost hunt. The classic 'club story' form.

Carnacki the Ghost-Finder is a hybrid of the detective story, the horror tale and the scientific romance. Up until then, most ghost hunter stories had been a mixture of the first two (and sometime scorned by both genres because of it), but now Hodgson was throwing in technology as well. Carnacki turns up to his investigations armed literally with a box of tricks. Although these include the accoutrements of traditional magic and the obligatory book of arcane knowledge -- in this case The Sigsand Manuscript -- there is also the Electric Pentacle, a defence of glass vacuum tubes which glow a pale blue when connected to a battery, thus keeping all but the biggest and hairiest bogles at bay during a vigil in a haunted room. Likewise there's an apparatus which throws out "repellent vibrations", a modified gramophone that records dreams on graph paper, barriers of concentric rings of glass tubing that glow with a mixture of defensive colours, and something with a passing semblance to a CD Walkman. (In 1910?)

The novelette "The Hog" with its Lovecraftian (actually pre-Lovecraftian) theme of the Outside reaching into our world, I had to read more than once to get a hold of what was happening. Others like "The Haunted Jarvee" and "The Searcher of the End House" read like a series of special effects with no real answers at the end, a breed of story that can leave the reader either infuriated or agreeably tantalised. Most disappointing (for me at least) were the stories that had no supernatural aspect, but turned out to be human trickery -- a form of story whose only reason for existing appears to be to jump up at the end and shout: "Tricked ya!" Others had sham hauntings running parallel to the real thing. This can be pure cliche in clumsy hands, but Hodgson pulls it off well. A particularly good example is in the final pages of "The Horse of the Invisible" where the unmasked trickster and his captors realise that what's coming clungk clunk down the dark passage towards them has no human hand behind it.

And then there was "The Whistling Room" -- a story of a uniquely haunted Irish castle which proved to be that long forgotten school-library-Alfred-Hitchcock-anthology story -- with its face at the window and huge lips erupting from the floor.

At about the same time, this same recognition of this same story in the same book was being enacted on the other side of the world. But it would be sixteen years before I learnt of it.

#

Over the years I sought out other work by William Hope Hodgson. During another hot summer I sat down in front of an electric fan switched to 'high' and read The House on the Borderland. Later I read Hodgson's sea-going novels The Boats of the Glen Carrig and The Ghost Pirates -- the latter so intensely written that I could feel the swaying deck beneath me. I never attempted his massive apocalyptic novel The Night Land because of its pseudo 18th century narrative voice. Many who have braved this awkward writing style (while shaking their heads and muttering "Why? Why? Why?") nevertheless declare Hodgson's genius at the book's concepts and inventions. I'll just take their word for it.

Back in the good old days it was easier to make a living as a short story writer than as a novelist. It was the heyday of the fiction magazine, all hungry for material. Hodgson -- amazingly prolific during the fourteen years of his writing career -- was a regular contributor to the publications of the day: horror, science fiction, straight adventure, romance and even westerns. Yet, apart from the Carnacki stories, which have been seldom out of print since 1972, there has been only one mass market paperback collection of Hodgson's short fiction: Masters of Terror Volume 1: William Hope Hodgson, Corgi, 1977. (It was just as well Hodgson appeared in volume one, as the publicised Masters of Terror Volume 2: Joseph Sherridan Le Fanu never eventuated.) Hodgson's short fiction survives today only in horror anthologies and in limited edition collections from specialty presses such as Donald M. Grant and Arkham House.

One Hodgson book I searched for in vain was a second volume of Carnacki the Ghost Finder. I didn't find it because it didn't exist. I'd been tricked into believing there were further stories due to a habit prevalent among detective story writers of the Victorian and Edwardian period: in the middle of a story they would make reference to some other case, the details of which they would subsequently tell you nothing. Some find this annoying (Conan Doyle in his Sherlock Holmes stories is perhaps the most famous offender), though it does lend a certain veracity or false history to a series of connected stories. So it is with Carnacki: "It is most extraordinary and different from anything that I have had to do with, though the Buzzing Case was very queer too"; "Do you remember what I told you about that 'Silent Garden' business? Well this room had just the same malevolent silence"; "I gave him some particulars about the Black Veil case, when young Aster died. You remember, he said it was a piece of silly superstition and stayed outside. Poor devil!" We hear nothing more of these cases, nor of the others mentioned in passing: the Noving Fur, the Steeple Monster, the Nodding Door, the Grey Dog, the Dark Light, the Yellow Finger Experiment and "that case of Harford's where the hand of the child kept materialising within the pentacle and patting the floor ... a hideous business."

It left me hungry.

So one day in 1990, with utter presumption, I started writing a Carnacki story of my own with the title "The Silent Garden". It was my first attempt at pastiche, but I'd read and re-read most of the Carnacki stories, and had a liking for Edwardian and Victorian ghost fiction to begin with, so I felt sure I could get away with this impersonation. Yet the project was accompanied by a twinge of audaciousness. Here I was picking up an idea discarded by a famous writer of the golden long ago, and daring to borrow his characters and writing style. Who'd a thunk!

Who? The answer was on the other side of the planet, and pure blind chance -- a six billion to one shot -- was about to lead me straight to it.

#

There was a time when I thought the answer was August Derleth.

The first edition of Carnacki the Ghost-Finder was published by Eveleigh Nash in 1913. It contained six stories -- all that had so far appeared in magazine form. The full nine story edition did not appear until 1947 when it was reprinted by Mycroft & Moran, the sister imprint of Arkham House, in the United States. Of the new additions, "The Haunted Jarvee" had been submitted by Hodgson's widow, Bessie, to The Premier Magazine and appeared in 1929, eleven years after her husband had been annihilated by a German shell while manning a forward observation post near Ypres, Belgium. The other two were "The Find" and "The Hog", neither previously published. The sudden appearance of these two, twenty-nine years after their author's death, at times aroused suspicions that they were not genuine Hodgson at all but pastiche perpetrated by August Derleth. Derleth was not only the owner of Arkham House and Mycroft & Moran, but also a well-known writer of weird fiction himself who often worked in the field of literary pastiche: Lovecraft, Doyle (Sherlock Holmes), and once even Sherridan Le Fanu. The perfect suspect.

However the truth lay in mundane commercial reasons. Though both stories are indeed genuine Hodgson, neither had ever sold despite aggressive marketing by Bessie Hodgson of all her husband's works between the time of his death in 1918 and her own in 1943. There's no mystery as to why this was. "The Find" is a weak piece involving an ordinary fraud, the story line having strong echoes of Poe's "The Purloined Letter": ie, hide the sought-after object in plain sight. As such it jars badly with the other stories of supernatural detection. "The Hog", though, had a different problem. This is a powerful novelette of intruding cosmic entities -- similar to and anticipating by many years the Cthulhu Mythos tales of H. P. Lovecraft. However at more than 13,000 words it would've been too big for what most magazines of the time considered the proper length for short fiction.

So I had not been beaten to the punch by August Derleth. But I would soon find I was not alone in my curious notion to fill in the gaps in the Carnacki canon.

In November 1990 I sent my pastiche "The Silent Garden" to Dark Dreams, a small press magazine in the U.K specialising in supernatural fiction. They accepted it a month later. In fact on the day their acceptance arrived I had started a second Carnacki pastiche based on a line from "The House Among the Laurels": "He had heard of me in connection with the Steeple Monster case." This was a fateful choice as it turned out. Because what was about to happen would never have done so had I picked on some other untold case to make a story.

Steeple ... a church ... a bell-tower ... a monster in a bell-tower ... church bells effecting the monster ... "Whoa, wait a minute," I thought. It'd suddenly hit me that this story line was straying too close to one I'd recently read, "Immortal, Invisible" by A.F. Kidd (a well-known writer in the British supernatural small press), where a church bell was used to exorcize a spirit. "Hmmm, don't want to look like I'm plagiarising ... and come to think of it, what do I really know about bell-towers anyway? A.F. Kidd writes about 'em, is in fact a bell-ringer herself, according to her magazine bios. A collaboration would solve both problems." So I wrote to her, outlining my difficulties. "Would you like to help me write this?"

Somewhere behind me, unheard, the shade of William Hope Hodgson chuckled.

A.F. Kidd proved to be the pen name of Chico Kidd. I discovered this when her reply came with the first post of 1991: "Dear Rick, This has got to be the longest the proverbial long arm of coincidence has ever reached (between Australia and England?). I had my battered copy of "Carnacki" down from the shelf not two days ago to look for a chapter heading quote for the book I'm working on, and it reminded me that I have some pastiches somewhere ... " (my emphasis). Circumstances had dictated that I write to the only other person on this planet to have written Carnacki pastiche. I should have such luck in lotteries!

When the initial shock had worn off we set about our project, and after six months of to-ing and fro-ing in the international mails "The Steeple Monster" was born. During this correspondence I found that Chico had likewise first discovered Hodgson and his ghost-finding creation in "The Whistling Room" likewise read in an Alfred Hitchcock anthology borrowed from a library. The "battered copy of Carnacki" she'd mentioned in her letter was the same Panther edition as mine, bought at about the same time that I'd wandered innocently and unsuspectingly into that Canberra newsagency in January 1975. Chico's stories had been written some years before mine, but without any thoughts of publication and so left to gather dust in a drawer.

"The Steeple Monster" was sent to the then new Australian SF/F zine Aurealis where it was published in the seventh issue.

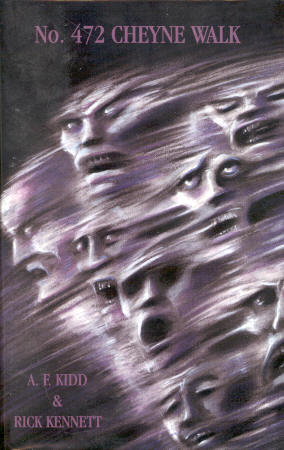

Meanwhile back in England, plans were going ahead to publish all our Carnacki stories in booklet form via the Ghost Story Society in Liverpool, of which Chico and I were members and to which Dark Dreams had relinquished its claim to "The Silent Garden". "The Steeple Monster" was accepted as a reprint, and Chico's "The Darkness" (The Black Veil) and "Matherson's Inheritance" (The Noving Fur) were brought out of their drawer and dusted off. The resulting 32 page booklet, 472 Cheyne Walk -- Carnacki: The Untold Stories, appeared in 1992, was distributed free to members of the Ghost Story Society and sold to anyone else for about one pound fifty. The small print run quickly disappeared. (Since then I have only seen one copy for sale. Found in England via the ABE web site in late 2001, it was going for around twenty pounds. Within two weeks it had gone.)

Over the years, Chico and I went our separate literary ways while our copies of Carnacki the Ghost-Finder and 472 Cheyne Walk sat quietly on our shelves. During this time Chico published two more Carnacki stories in the British small press: "The Case of the Grey Dog" (an early pastiche not included in the 1992 booklet) and "The Witch's Room" (written subsequent to the booklet). Chico then suggested I try writing a story set in Australia during Carnacki's early days as a sailor. It has been noted that Hodgson based a great deal of the Carnacki character on himself. In "The Haunted Jarvee" for instance he demonstrates a familiarity with ships and the sea: Hodgson had spent eight years -- from 1891 until 1899 -- in the Merchant Marine and had visited Australia at least once. Unfortunately I couldn't get the story to work and it soon bogged down. It was eventually finished in collaboration with Bryce Stevens as the stand-alone gaslight Gothic "Rookwood" which, like "The Steeple Monster" collaboration before it, also found a home at Aurealis.

Despite this setback the idea of writing more Carnacki stories wouldn't go away. In addition the Ghost Story Society, which had moved from England to Canada in the mid nineties, had sprouted a book publishing arm: Ash Tree Press. Here were distinct possibilities. By coincidence -- a word that had been our constant companion throughout our work together -- Chico and I got the same idea at the same time: write more stories, put 'em in a book.

Ash Tree was contracted. They indicated interest in the project.

Thus encouraged we began another collaboration based on almost the last line of the last Carnacki story Hodgson ever wrote: "Some evening I want to tell you about the tremendous mystery of the Psychic Doorways." After a page or two I left Chico to finish "The Psychic Doorway" under her own name while I had another crack at Young Carnacki in the Colonies, ending up with a story called "The Roaring Paddocks." Having now worked up momentum, Chico penned "The Sigsand Codex", detailing Carnacki's initial discovery of his oft quoted book of arcane knowledge; and I sent him out to sea in the service of the Royal Navy to encounter "The Gnarly Ship", an omen of the coming war which would engulf the original author of these tales. Finally, in a break with format, Chico allowed one of the visitors to Cheyne Walk to take the floor in "Arkright's Tale", while I, seizing one of Chico's stand-alone ghost stories by the plot line and inserting Carnacki as the protagonist, reinvented it as the novella "The Keeper of the Minter Light."

And so there we were, slumped over our respective keyboards, vaguely aware that coincidence, striking once again, had arranged for our contributions to this 99,000 word collection to be almost exactly equal.

In May 2002 Ash Tree sent us the final drafts for corrections. At the end of June 472 Cheyne Walk -- Carnacki: the Untold Stories appeared as a 242 page hardback in a print run of 500 copies.

Such are the consequences of walking into a Canberra newsagency in 1975 and finding a Panther paperback. Such are the consequences of blindly writing to the only other person in the world working along similar lines. Such are the workings of synchronicity and coincidence.

©2020 Go to top