MirrorDanse

MIRRORDANSE BOOKS

Year's Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 1, 2004

Year's Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 2, 2005

Year's Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 3, 2006

Year's Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 4, 2007

MIRRORDANSE EDITIONS

OTHER BOOKS

SAMPLE STORIES

Cigarettes and Roses, by Ben Peek

The Desertion of Corporal Perkins, by Bill Congreve

The Hours Before Sunrise, by Bill Congreve

The Mullet that Screwed John West, by Bill Congreve

RESOURCES

2005 short fiction (pdf)

2006 short fiction (pdf)

The World According to Kipling

(A Plain Tale from the Hills)

by Geoffrey Maloney

First appeared in Aurealis #25/26

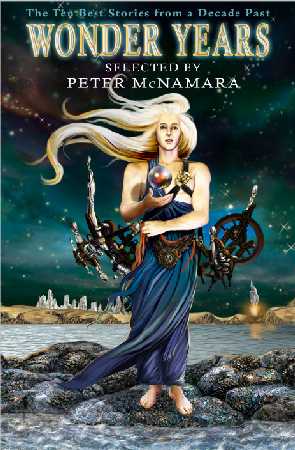

Reprinted in Wonder Years

Copyright © Geoffrey Maloney, all rights reserved

Winner: Aurealis Award for best fantasy short.

On a hot humid afternoon shortly before the monsoon was to break, Captain Frederick Youngburton, returned barely three hours from the North-West Frontier, was relaxing on the verandah of his hotel sorting through his mail. One of the letters was from the writer Kipling requesting permission to interview Captain Youngburton for a novel that he was writing on the Great Game. Utmost secrecy is assured, Kipling wrote, and this brought a chuckle to Youngburton's lips. Mr Kipling was a young man, brash and arrogant, who thought he knew India, but who had never managed to delve deeper than the gossip provided by ladies at dinner parties and the cheap talk of tonga-wallahs who had carried him home afterwards. Youngburton was about to dash off a suitable reply when a hotel servant in an immaculate red coat came running along the verandah with a stiff cream envelope in his hands.

It was a message from Captain Fleming at Barrackpore Cantonment requesting Youngburton's attendance urgently. To assist with a matter of utmost importance that had suddenly arisen, Fleming had written in an erratic hand. Youngburton sighed; he had expected a few days grace before anybody realized that he was back in Calcutta again.

#

When Youngburton was shown into the captain's office at the Cantonment, Fleming moved around his desk quickly, his thick floppy moustache quivering like a frightened rabbit upon his lip. Youngburton had not met Fleming before -- Fleming was a desk captain whose knowledge of India pertained to Calcutta and its immediate environs -- and he suddenly felt awkward in the company of such a gentrified man whose fingernails were manicured just so. Youngburton's own hands, thick calluses, split fingernails and a shortened finger, matched those of any horse or elephant trader's across the length and breadth of British India.

"It is a pleasure," Fleming said, extending his hand, "I have long admired the work you did at Peshawar."

"I am fortunate in that our Majesty provides me with interesting work and I am able to do what is required," Youngburton replied.

"I think you do more than is required and that is why I am glad to have you here. Dr Roberts insisted that I contact you about this matter. You know him I think," Fleming said, grabbing Youngburton by the elbow and escorting him across the room.

"Yes," Youngburton replied, easing himself out of Fleming's grasp, "we went to Sandhurst together; we have managed to stay in touch over the years. How is he?"

"At this moment," Fleming said taking Youngburton's elbow again and leading him out the door and across the verandah, "Dr Roberts is ensconced in the infirmary with the doors sealed fast and we have been unable to get him to open them again."

"The reason being?" Youngburton asked when Fleming failed to offer any further information.

"The monsoon is late," Fleming said, as if that explained it all.

"I fail to see ..." Youngburton said, as they made their way across the cantonment's parade ground.

"Yes, of course you do, but the doctor goes on a binge from time to time. It is this humidity that does it to him ..."

Dr Roberts's fondness for whisky was well known. It was a fact of the man, not of the erratic nature of the Indian monsoon.

"I doubt you asked me here for the sole purpose of advising Dr Roberts to stop drinking," Youngburton said.

Fleming quickened his pace and flapped his left hand in the air as if encouraging Youngburton onwards. "Dr Roberts is presently engaged in an autopsy. We believe that it is the body of a special agent who was working for Prince Prokoliev of St Petersburg," he said.

"Many of Prokoliev's agents have been engaged and neutralized. An autopsy was not required. The cause of death in all cases was obvious. Death by assassin or assassins unknown is the usual official response."

"Yes, well ... this one is different. It appears that we have not had a hand in it. The body was found on a Himalayan track, east of Darjeeling, just outside the village of Sandakphu. The local untouchable castes refused to bury it, believing because there were no signs of decomposition, that it was a demon and being the superstitious lot they are, word soon spread and many began to leave their villages. The body was brought down after the local Commissioner sent a man up to investigate the nature of the rumours."

"It is certainly of a curious nature, but I am none the wiser as to the importance of it or as to why you asked me here."

"That is what Dr Roberts is supposed to be explaining," Fleming said, his whole manner now reminding Youngburton of a rabbit, one that wished to turn tail and seek the safety of its burrow.

When they arrived at the infirmary Youngburton and Fleming found an Irish sergeant and several Indian privates gathered around the doors as if in a state of apoplexy.

"Obviously, you have had no success in persuading Dr Roberts to open the doors," Fleming said.

"No Sir, but we have managed to ascertain the reason for the doctor's behaviour."

"He is drunk!" Fleming said.

"Well, Sir, apparently the body that the doctor was inspecting is lying between the door and the position that the doctor has currently taken up in the room. He refuses to pass the body because it is still alive. He claims that he locked the doors to protect us."

Fleming turned to Youngburton with a smirk upon his face that seemed to say, 'You see he has been on a binge again'. But Youngburton wasn't interested in the reasons for the doctor's behaviour. He was losing not a little patience with the escapade that they were engaged in. He unclipped the cover on his holster and pulled out his gun. It was an Adams twelve barrel repeating revolver, one of the more innovative weapons to emerge in recent years. He looked at the heavy wooden doors of the infirmary and the large bronze locking mechanism that held them together, dialled the revolver for three barrels, and blasted away. The three bullets hit simultaneously. The lock shattered, the doors shook, then parted.

Dr Roberts was cowering in the far corner of the room, a shiny figure with an array of cuts and scratches glowing wet and scarlet in the shaft of sunlight that hit him from the small window vent. His eyes were round and wide, unblinking, and it seemed that he was frozen as if he feared to take a breath.

The body which was the source of the confusion lay just inside the door. It was that of a young native man, his skin the colour of coffee, but as Youngburton kneeled down to take a closer look, the corpse suddenly came alive and raised its right arm as if to strike him.

"It is a mechanical demon, Youngburton," Dr Roberts cried out. "I have disabled its legs, but you would do well to despatch it completely."

The corpse looked at Youngburton, then rolled towards him and lashed out with its left arm, but by now Youngburton was a safe distance away. It rolled again and this time it revealed its stomach. Youngburton saw the skin had been cut away during what he presumed was Dr Roberts's autopsy. He had seen many dead men sliced open and many living as well and would never forget the slime and smell of the intestines as they spilled out of the body cavity. But nothing spilled from this creature. Instead he saw the bright clean colour of grey smooth metal and the intricacies of many small gears like those found in a watch and, as he listened closely, he could hear a whirring sound as if the machinery within this creature was coming alive again. He had not seen anything like this before, but put a bullet through the main chest cavity believing that that would do the essential damage as it would to any living creature.

Two

That evening Youngburton took a private dining room at the Calcutta Turf Club. When Roberts arrived, Youngburton was pleased to see that not only did he appear substantially recovered from his ordeal, but that he was sober as well. There were many fine cuts across his face, and no doubt his body, where the creature had bitten and scratched him during the initial stage of the autopsy, but unless they ran septic it was likely they would heal within the week.

When they were half-way through their meal -- a leg of mutton which had been slowly basted in yoghurt and cardamon, the doctor drinking only water with a nervous shake of the hand, Youngburton indulging in several glasses of claret -- Youngburton said, "So tell me what you know of the origins of this creature."

Roberts looked up from his lamb, eyed Youngburton's glass of claret enviously, smiled a sad smile, then said, "Ever since Shelley wrote that damned Frankenstein, scientists across Europe, including a number of British doctors who should know better than to fool with the laws of nature, have been attempting to turn fiction into fact. Some have foolishly trode the path suggested by Shelley, attempting to reanimate bizarre conglomerations of dead flesh into a living being. Others less foolish, but none the wiser, have chosen to work with mechanical devices. I remember a wondrous dancing bear at the Great Exhibition in London when I was a child. It was part of the foreign exhibits, one manufactured by Peter Prokoliev himself when he was a young inventor and had not yet risen to lofty status of honorary prince and head of Russia's military laboratories in St Petersburg. It appears that the Prince has now surpassed himself. The intricacy of the gearing in the body shows great skill, skill which we do not currently possess and perhaps never will."

"You know for certain that it is a Russian device?"

Dr Roberts nodded his head. "Some of the internal workings I had examined, prior to inadvertently reanimating the creature, bore the trademarks of a factory in St Petersburg. Given that is where Prokoliev's laboratory is situated, I think it is more than a fair assumption on my part."

"Indeed," Youngburton said. "How long do you suppose it would have taken Prokoliev to produce a creature like this?"

"Years," Roberts said, "maybe two, maybe three, perhaps more. The skill that is required is almost beyond my comprehension. If you could imagine a watchmaker building a thousand watches, then building a thousand more, then linking all those watches together with yet more gearings and devices so that all worked in complete unison with each other, all kept the same time at the same moment, then you may get close to understanding how complicated and perverse this thing is."

"So there cannot be many of these creatures out there?" Youngburton said, seeming to relax a little.

"I would say that we have found the only one and there are no other creatures like this out there at all. Prince Prokoliev has shot his arrow and we have broken it."

"But one creature, built at great cost, so much time and effort, what would the Russians hope to achieve? Is it merely to frighten us, an attempt to prove to us that their technology is the greater."

"It is a red herring and nothing more. It sets us chasing hares while the Russians plan something altogether different. That would be my sober opinion on this strange matter," Dr Roberts said.

"And your unsober opinion?" Youngburton asked.

Dr Roberts smiled. "After we have finished dinner tonight, I shall retire to my study and within there I will sip, sip, sip and fill and sip, sip, sip again and fill again. Despite what Kipling has said against drinking in private, I could never abide getting drunk in public. Besides I believe that it stimulates the intellect. I imagine that I am one of the lost souls of Kipling's Empire and, once I am drunk, I will imagine that Prokoliev has hordes of these creatures out there just waiting their opportunity to undermine and overthrow the might and power of British India."

'You would do well to steer clear

of Mr Kipling's fabrications and rectitude. There are some who say that he is as dangerous to the health of India as Prince Prokoliev. Kipling undermines us by holding up our small faults to close scrutiny and causing us to look too deeply inwards when we should be looking outwards to the enemies that hover on our borders."

"And there are some who say that Kipling is a genius, that he understands everything that we do, that he writes our past, our present and even our future for us," Dr Roberts said without a trace of a smile on his face.

"There is only one man I trust with the future and his name is not Kipling," Youngburton replied.

His name was Sarat Chandra Das and he ran a small photographic cum fortune-telling business deep within the narrow streets, twisting alleyways, obscure corridors and shuddering humanity of the great city of Calcutta. After dinner at the turf club, Youngburton hailed a tonga and had the wallah take him to Das's place. But before he bid the Doctor goodnight, he said, "This creature you examined, do you think it was once possessed of intelligence?"

The doctor sighed. "Nothing in this enterprise would surprise me, dear Youngburton, nothing at all. When fully animated there may be no distinguishing it from any other man."

#

Das was in his darkroom when Youngburton arrived, and he was forced to wait in the lounge area, an open verandah along which the whole world seemed to pass by. There were new pictures on the walls of the verandah, or at least ones that Youngburton had never noticed before. One in particular caught his eye. It was a photograph of a skinny man, dressed in white robes that revealed much of his dark skin beneath, a pair of gold-rimmed glasses perched on his nose, a man of almost regal bearing with a piercing serenity in his eyes. In one hand he held a handful of white powder which on closer inspection appeared to be salt. His arm stretched towards the camera as if this handful of salt was of the utmost importance.

"Who is that man?" Youngburton asked when Das appeared. The shortened end of his index finger traced a line in the dust across the photograph's glass covering. The tip of that finger, now withered and grey, lay in the satin interior of a small black enamel box in the possession of a magician somewhere in the outer regions of Mongolia. It had bought Youngburton his freedom once.

Das, still blinking his eyes from the dark room, looked up at the portrait. "I call him the naked fakir. As to who he is, or what he shall do, who am I to ask or answer such questions? I merely record what my science through my camera reveals to me."

Youngburton felt a chill at the base of his neck as he followed Das through into his small studio. He placed Youngburton before his camera, got him to strike a pose, something befitting of a man of his age and stature, then ducked beneath his dark cloth. Just before Das squeezed the camera's bulb, Youngburton thought of what he had seen in Dr Roberts's infirmary. He wondered about these creatures who were men, yet not men, wondered whether they had souls, had thoughts like he did, wondered how they would appear in the eyes of God, but more importantly wondered if they were a real threat to Pax Britannia, or if he was about to start chasing hares as Dr Roberts believed.

When the photograph was developed, Chandra Das emerged from his dark room shaking his head and speaking in a tone that bespoke of a longstanding friendship. "Freddie, Freddie, Freddie," he said. "It seems that you have nothing but romance on your mind."

Youngburton tore the picture out of Das's hands. It showed him as he was, as he had been when the photograph was taken only minutes ago but, next to him, dressed in a beautiful evening gown, was a woman with blonde hair piled upon her head. The features of her face were so immaculately carved that she looked perfect, as if she were a doll and not a woman at all. Barely visible, as if the photograph was a century old, you could make out a building in the background and, behind this, sharply rising hills. There was something about the background that was familiar to Youngburton and as he studied it, and his eyes absorbed more detail, he recognized the building as Christ Church at Simla. The church he had seen before, it had been built during the year of the Mutiny, but the young woman stirred nothing in his memories.

"She is beautiful," Das said.

"But what does she mean to me?"

Das shrugged. "She is your future. The one you will marry, the one you will die for, the one you will love and lose. Or perhaps you will kill her, or she will kill you. This is a picture of great passion. Every time a woman appears standing next to the subject, great passion is involved. And this time I have a good feeling. I think the passion is love."

"You should go back in the game, Sarat," Youngburton said. "Your talents are wasted in this street alley."

Was there a touch of sarcasm in Youngburton's voice, was he scared of what the future might reveal? Chandra Das could not make up his mind. He had known Youngburton for years, they had worked at Peshawar together, but still he was a man who could not be known. So much of him dwelt beneath the surface, in an eternal twisting ferment, Das thought, suspecting that Youngburton had passed through each of his lives never learning from anything that had gone before.

"I am too busy making money," Chandra Das finally replied, but looked again at his picture of the naked fakir.

"That man, why does he intrigue you?" Youngburton asked.

Das hesitated, seeming to weigh something up, then shrugged. "I took a picture of a map of British India and this is what it revealed to me."

"I do not like the look in his eyes. There is too much wisdom there. He knows how to lose and how to win and how to keep struggling for what he believes in. He is a dangerous man. If we knew who he was we would have to arrest him and keep him behind bars for the rest of his life. I will forget that I ever saw that photograph," Youngburton said as he stepped down into the street and waved up a tonga.

Three

Despite Das's prediction, romance was not on Youngburton's mind when he arrived in Simla, although romantic thoughts still occupied the minds of a considerable number of the young women who found themselves marooned at the hill station due to the failure of the wretched monsoon. Youngburton took a room at the Hotel Cecil under the name of Francis Anderson, an Assistant-Commissioner at Kala Ganj -- one of the more obscure districts of the far-flung mofussil -- a district that nobody would know about but one still interesting enough to allow room for invention. As Anderson, Youngburton's first action, after checking into his room and arranging his personal belongings, was to send his card to the unofficial maharani of Simla. Mrs Hawkesbury was a widow of uncertain age who had taken up almost permanent residence at the hill station following the untimely death of her husband in the Mutiny. That had been many years ago and now, through a shrewdness of character, a determination of will, and a nose that could not keep out of other people's affairs, she had enshrined herself as the 'matchmaker' of the hills. She could just as easily arrange a marriage as a mere flirtation, or even a dalliance with a married woman grown bored with her too hard-working husband. Everybody believed they knew her secret -- the romances, the affairs, even the scandals she arranged -- and everybody, right up to the Viceroy himself, kept her secret, so highly were her skills in this business regarded. Which was just as well, for the secret that everybody knew hid another: the fact that Mrs Hawkesbury, since her arrival in India at the tender age of eighteen, had been actively employed by the Indian Secret Service and was well versed in the verisimilitudes of the Great Game.

#

When Francis Anderson was shown into Mrs Hawkesbury's garden, he was greeted as a long lost friend. "Francis, my dear young man," she said. "How lovely to see you."

Anderson moved forward and gave her a kiss on the cheek. As he did so, he whispered in her ear, "Is the garden safe?"

She blinked her eyes back at him twice in quick succession. In a louder voice, he said, "I have something private to discuss with you, madam. It concerns a certain lady of my acquaintance."

"As with so many young men who come to my garden," Mrs Hawkesbury said as she smiled. "Perhaps we could take a little walk, you and I, up to the lookout. I have heard that the sky will be clear this afternoon. Perhaps we shall see the snow upon the mountains."

They smiled at each other as they exited through the back gate and began the steep climb up into the hills. When they arrived at the lookout, Youngburton said, "There is a body lying in Calcutta the like of which has never been seen before. It is dead and yet not dead. It is made of flesh that is not flesh and its internal organs are entirely made of metals and small gearings as delicate as those to be found in a watch. It is clear that this creature is some Russian device hatched from the laboratories of Prince Prokoliev in St Petersburg. The strategic question is whether it is one of a kind, a mere phantom sent to torment us, a subterfuge, or whether it is part of some larger plan the Russians are hatching. I would be interested to hear any unusual stories that have come your way from the young men that have passed through your grasp."

"Through my grasp! A rather inelegant way of putting it, as though am I am some bordello madam set to take her clients for every penny they may be worth."

"You know I did not mean it that way."

"Perhaps ... still I have heard an interesting tale not too many months passed. There was a young gentleman here who had been to Manali and back. He told of a convent in the north that was said to be petitioning the Vatican for the first Indian saint. The story goes that the young lady was a model of virtue who came to an untimely end. Her body was laid in the church and it lies, they say, as it was laid -- in perfect condition. It has not corrupted. The local natives had begun to flock to the church and it is said there has been much conversion to Christianity as a consequence. It sounded like the perfect tale to guile the superstitious and get a few runs on the board for the local mission. I thought not much of it until now."

As always, Sarat's talents had proven themselves, Youngburton thought. It was the reason he was in Simla, driven by the photograph of a woman who, no doubt, did not exist. But nonetheless it had brought him here and brought together the vital pieces of information that had been drifting in the ether. Youngburton could see the implications. The thought of the Vatican gaining a hold on the masses of the subcontinent ... a mass conversion of Hindus and Muslims alike would certainly weaken the increasingly fragile hold of the British Empire. He was surprised that Mrs Hawkesbury had not made similar connections and he wondered whether she had been in the Game too long, whether she was losing her eye for the ever important detail.

Youngburton took Chandra Das's photograph from his pocket and showed it to her.

"This is what brought me here," he said.

Mrs Hawkesbury smiled, a charming smile that returned the beauty of her youth to her face. "I know her," she said. "Her name is Alice Landys-Haggarty. Her husband is stationed at Coimbatore in the south, a dreary place I hear by all accounts. She is here, apparently, under doctor's orders, but whether that is to improve her health or her social life, I will let you be the judge when you meet her."

"I am not here for a dalliance," Youngburton said, and added because he wished to hide the surprise that he felt, "I show you this photograph merely because it intrigues me."

"Sarat's skills intrigue us all. What is the man up to now?"

"Predicting the future," Youngburton said.

"When has he never done that?"

"Of India," Youngburton said. "He showed me a photograph of the man who would be king, of the man who would rule India when our time was up. He seemed such a humble man, such a gentle man, yet behind his eyes there seemed the intelligence and wisdom of centuries."

"Oh, Freddie," Mrs Hawkesbury said with a laugh in her voice, "I hope you aren't going native on us. It has been the ruin of many a young man."

"I am beginning to fear that we are but caretakers here," Youngburton replied.

"More like parents with children," she said. "Perhaps one day India shall be for the Indians, but I hope I do not live to see it. I wish to leave India as I know it; India shall not leave me. That is my destiny, I am sure of it, right down to my bones. But where, dear Freddie, does your destiny lay?"

She had asked this question lightly, but he did not take it lightly. "Sometimes," he said, "I look at the moon and the stars and I know that some day we will be out there. There is talk in London and Paris, in scientific circles, that it might be possible by the turn of the century to send a man to the moon. In whatever small way I would like to be part of that. That is where our destiny is, beyond this planet of ours."

"And pigs shall fly," Mrs Hawkesbury said.

Four

With the introductions of Mrs Hawkesbury, Mr Anderson found himself drawn into a round of garden parties, picnics and special events. One such event was the archery tournament at Annandale racecourse which was arranged by Commissioner Saggott with the purpose of bestowing the prize, a diamond bracelet, (so the gossip would have it) upon his beloved -- a certain Miss Beighton who was reputed to be the best woman archer in all of British India. (Youngburton, by contrast to Francis Anderson, was busily planning the long ride up to Manali. In between social events he was organizing supplies and haggling in the bazaar for a suitable mount.)

It was after the archery tournament (at which Miss Beighton unfortunately failed to prove her prowess) that Youngburton first met Mrs Landys-Haggarty. The first thing she said to him was, "Do you care for Kipling, Mr Anderson?"

Looking at her in the flesh, Youngburton thought the likeness to the photograph that Sarat Chandra Das had taken was so striking that for a moment he was lost for words. He had never much cared for fair-haired women, but Alice Landys-Haggarty was one of the most striking women who had ever crossed his path: her features were so finely cut; her skin so immaculate, like porcelain, translucent, like the skin of no other person he had ever met before, it held not a single blemish. It was some time, therefore, before he could gather his thoughts to say, "I met the man once. I'm afraid I care neither for him or his work. He seems intent on creating a view of India that bears no resemblance to the reality that I know, yet somehow it becomes the praxis of our lives."

He felt, despite the truth of his words, that he had spoken too harshly, that he did not know the right thing to say to create a pleasant impression and generate congenial conversation which he was convinced was the only sort of thing that young ladies were interested in.

"I know what you mean," Mrs Landys-Haggarty replied, linking her arm through his. "I sometimes feel that I'm living in a Kipling story. Most people around here think that he's some sort of god. They read him religiously and seem to act as he would have wanted them to act had they been but characters of his. It's as if they read his stories before he has written them and adapt their behaviour accordingly."

"So that Kipling writes our past, our present and even our future for us?" Youngburton said.

"Cleverly put, Mr Anderson," Mrs Landys-Haggarty replied and gave him such a sweet smile that Youngburton began to believe that the art of congenial conversation was not entirely beyond his grasp.

Five

"There is nothing for it, Freddie, but that you must take her to your bed," Mrs Hawkesbury said. "That is what she wants, what she has come here for, a dalliance that will ignite the fires of romance and give her something to dream about during the next nine months she shall spend down on the plains with that boring husband of hers. You have been called, dear Freddie, now you must act upon it as any man in your situation would. You cannot deny that she is beautiful. Imagine that body stripped bare, what further beauty it has to reveal to you, her chosen one. She is so delicate, so magnificent, so exquisite and you are just the man to take her, spread her legs, quench her thirst. Besides, my reputation is at stake."

Youngburton lay on the bed. A sense of languor soaked so deeply into his body that he feared he would be unable to move should he wish to. Mrs Hawkesbury stood at the window, gazing out on the quietness of the hills. She was naked and, at her age, no longer felt any shame at that. She would have paraded naked down the Mall of Simla if she thought that would have achieved anything for her or those that she supported.

"Really, Delia, sometimes you speak too crudely," Youngburton said.

"Even for you? It did not seem to upset your sensibilities a moment ago, when we were in the throes of it. Then your passion was stirred by the words I spoke to you. So now I speak as honestly to you as I spoke then. Let Alice have her dalliance."

Youngburton sighed. "I think that you have read this one wrong," he said.

"Come tomorrow in the afternoon, at four. She will be here waiting for you. Afterwards we shall all have dinner together."

"Tomorrow I go to Manali, to investigate that incident at the convent that you spoke of."

"You can go the day after. I am sure that the body will still be there, the nuns still mourning over it. If you do not come tomorrow, then you shall never know whether she came or not and knowing you, Freddie, I think that that shall bother you for some time."

Six

In the early hours of the morning, Youngburton rode his mountain pony north of Simla, heading it up into the rugged mountain passes that lead to Manali. He was dressed in native clothing and had darkened his face with a theatrical tan. He knew that he could never pass for a native and he had not been foolish enough to presume as much when he sat in his room at the Hotel Cecil diligently applying the make-up. His eyes were too blue, his forehead too long and his nose rather too robust. Still he hoped that he would pass as a half-caste, the son of a Scottish engineer who had whored in a native brothel once too often and yet had enough gumption about him that he had educated his half-caste son in one of the better schools that India had to offer.

The pony's breath frosted on the cool morning air and try as he might Youngburton could not keep his mind focussed on the task that lay before him. He kept trying to think how best to gain intelligence within the native town at Manali, and how to deal with the nuns once he arrived at the convent, but his mind kept wandering back to the previous afternoon when he had arrived at Mrs Hawkesbury's house at four as he had been instructed ...

He was shown through the front door of Mrs Hawkesbury's residence by an Indian servant, a gentleman so good at his job that he was practically invisible. Youngburton went straight up the stairs, to the room that he had been in the night before. Mrs Landys-Haggarty was sitting in a chair by the window, calmly reading a book -- sitting there, Youngburton thought, as if this was her house and it was her usual custom to sit there in the afternoon enjoying the cool breeze that flowed down from the hills.

"There is a story in Mr Kipling's latest book that is about you, Mr Anderson. It tells of your successes, your follies and how you trusted too much to the beauty of a pretty young woman," Mrs Landys-Haggarty said.

"That, my dear lady, sounds exactly like the sort of rubbish to spring from Mr Kipling's mind, and is the reason why I refuse to read anything that he writes."

"And I agree with you, mostly, but this one is different; you would be interested in this one I am sure, just as I am. It is called 'The Man Who Should Have Known Better'. Let me read it to you.

"'Captain Youngblood was one of those young men that you come across from time to time in India. He was dutiful to the Queen and respecting of authority to the extent that it was necessary. He carried out his duties faithfully, drank only in company, but lurking within him was something that said, 'This is not right, this is not what I should be doing.' Yet as to what he should be doing, Captain Youngblood had no precise idea, other than something very vague such as he wished to change the world for the better, or do great things. He believed the British Empire, in some form at least, would last forever, and that one day in the not too distant future a man, no doubt bearing the Union Jack, would walk upon the moon and beyond this that humanity would ultimately live among the stars. Noble sentiments in anybody's book, but difficult ones to bring into actuality. He was a man reaching beyond his time to a future that did not yet beckon.

"'Now a lesser man than Captain Youngblood would have been driven to drink as a result of his failed dreams and would have been content to hide that habit in private, sitting in his study, sip, sip, sip and fill and sip, sip, sip and fill again, a pleasant mantra for his confused mind. An even a lesser man, for want of any true purpose, may have considered making a tragic end of it, but not Captain Youngburton. This ...'"

"Enough," Youngburton said. "Kipling does not write my life!"

"But that is almost his very next line ... 'This gentleman you see did not believe that anybody was writing his life. He did not have faith in the church or God for that matter, nor his superior officers, nor anybody else that he happened to meet. So he only had himself to rely upon, himself and no one else and we all know how dangerous that might be, to appear to mix in company and to have friends and professed allegiances, but really within your soul to be a hermit, isolated and alone. Yet Captain Youngblood was oblivious to such dangers ...'"

"I cannot believe that Kipling wrote those words. There is too much depth for Kipling," Youngburton said. "He is a man who skates across the ice of complexity."

Mrs Landys-Haggarty closed the book. "Shall I read you more?" she asked.

"That is not why you are here," Youngburton said.

"No," she said and cast her eyes down towards where the book sat on her lap. "It is not why I am here. But why are you here, Mr Anderson?"

Youngburton felt as if he had been caught within a dream. For a moment, when she had been reading from the book, he had forgotten that he was still Frances Anderson. He had heard Youngblood as Youngburton and believed that she had connected the similar names together to make the sport that she had. Now he believed that she hadn't, that it was mere coincidence. She did not know who he was ... but why was he here? He was here for Delia, as simple as that; he owed her so many favours and while Alice Landys-Haggarty was beautiful and attractive and her figure exquisite and perfect in every sense, he did not desire her in the same way that he had desired other women, in the same way even that he had desired Delia the day before. But still he went to her and professed his love, went to her on his knees and buried his head against her breasts, as he imagined that Mr Francis Anderson would have done in this very situation.

"Mr Anderson, you embarrass me," she said, her arms coming down and pulling him in tight so that his ear was right over her heart. A man in throes of passion would not have noticed; he would have been so consumed by his natural instincts that he would not have even thought about it, but Youngburton was acting a role within a role: he was Mr Francis Anderson, then again he was Mr Francis Anderson pretending to be besotted with Mrs Alice Landys-Haggarty and, because of this, every moment in these roles seemed crucial to him. So he said to himself: I will lay my head against her breast, I will listen to the beating of her heart, I will tell her that I love her. But as he did this, as he moved through each preconceived motion acting out the part of Mr Anderson, acting out the part of a besotted lover, he suddenly became himself again as his ear snuggled between her breasts and heard, not the beating of a human heart, but only the whirring of many clockworks, the exact same sound that he had heard in Dr Roberts's clinic but a few days ago.

He sucked in his breath when he heard this; his heart quivering then beginning to beat rapidly. Then he did as he would have done had he not heard this thing, did exactly as he had planned to do when he had first entered the room. He mouthed words of love and comfort as he began to strip away her clothes, tearing away the layer upon layer that hid her body beneath. But now things were different. Tick-tock, like the sound of a clock -- he imagined himself with a doll, imagined that as he uncovered the layers and stripped her bare that he would caress her neck and run his hands across her breasts and down over the roundness of her belly, running them down between her legs, to spread her legs apart, and therein, between them, find nothing but a wedge of porcelain sealed away, a smooth white cold hard thing hidden there between her legs as he imagined that any doll would have.

He was surprised then as her breathing quickened beneath his touch, as his hand explored further, that she was as deep and soft as any other woman that he had known. And later, when she had taken him inside of her with an urgency that was unexpected, she had gripped him with such power and gave him such pleasure that he lay against her wondering what madness had driven the anxiety and suspicions into his mind.

They slept together until the evening, laying in each others' arms as the golden sun of the late Indian summer streamed in through the windows. Youngburton woke first and lay his head against her breast and, in that waking moment, with the soft golden light upon them he heard a heart softly beating.

#

Barely a few hours out of Simla, Youngburton pulled his pony off the main trail and took a track into Macarthurs Bazaar, a rough and ready little town tucked amongst steep hills, little more than a chai station for weary travellers. There, through kind words and silver touches upon the palm, he traced the British agent and commandeered the telegraph where he put a request through to Calcutta. He waited several hours, then more, and when the answer came back -- Mr Landys-Haggarty, Assistant District Commissioner at Coimbatore, unmarried, no children, deceased some three months from cholera -- Youngburton mounted his pony and turned it back on the trail to Simla. He thought he knew, but still he could not be sure. He remembered those moments in the late afternoon when he had willed a heartbeat into her body.

Wide-eyed and vulnerable, still in his half caste make-up and his clothes muddied from travelling, Youngburton pushed past the Indian servant and burst upon Mrs Hawkesbury as she was having tea with the Vicar.

"Where is she?" he said.

Mrs Hawkesbury rose up in a flurry of skirts, grabbed Youngburton by the arm and escorted him from the room as she mouthed pleasant 'excuse me's into the air. In the hallway beneath the stairs she released him. "Where is she?" he said again.

"She is gone," Mrs Hawkesbury said. "Down to the plains. Gone back to her husband as they always do. She left this morning."

Youngburton's hand went up and gripped Mrs Hawkesbury around the neck forcing her head back between the banisters of the stair railing. "Her husband is dead," he said, "dead for three months. Her husband is not her husband. The gentleman in question was never married. You should have known that. Where is she?"

Mrs Hawkesbury's eyes moved upwards, towards the top of the stairs. Youngburton smiled as he released his grip, his hand returning quickly into his robes to find the dagger that he had concealed there.

"What madness is this?" Mrs Hawkesbury said speaking in short sharp whispers. "You would kill her? You cannot. She is immaculate. As a woman, but more than a woman. You know this, you have lain with her, she is a creature of divine perfection."

"She has blinded you," Youngburton said.

"As she blinded you and you are the better man for it, although you do not know it yet. Why come back if it was otherwise?"

Seven

Alice sat by the window as she had the day before. "I knew you would come back," she said, before she turned to look at him.

Youngburton stood in the doorway with the dagger in his hand as she cast him a glance. "If you would kill me, Captain Youngburton, I would wish you do it quickly and painlessly. You may be surprised that a creature such as I feels pain, but I can assure you that I do."

Her hands went to her hair, pulled it up and twisted it atop her head. Her pale white neck cut such a delicate curve against the soft afternoon light.

"There is a flap," she said, "at the base of my neck. Beneath it you will find what the Prince calls my energy core. All you need do is open the flap and remove it. I can assure you that I will not resist."

Youngburton moved towards her, touched her neck, felt the softness of her skin that was not skin, but still he believed it to be like any other person's that he had ever touched. He caressed her neck softly, slowly.

"Does this please you?" he asked.

"It pleases me," she said.

"And yesterday when we lay together?"

"It pleased me as well ... you do not know how it pleased me to be held by you, to be held as a woman would be held, to be treated as ..."

"Enough ... that is not why I am here, I wish to know of that story you read me yesterday."

"... any other living creature ..."

"The story!'

"'The Man Who Should Have known Better'?"

"That is the one."

"What of it?" she asked.

"How does Mr Kipling finish it?"

"He does not."

"No?"

"No, because Mr Kipling did not write it ..."

"Who then?"

"I did."

Youngburton laughed. He did not wish to laugh. He felt that he was standing on the edge of something, something too big and too huge for him to fathom, and that if he were to take a step, reveal any emotion, then he would fall headlong into the future.

"You fancy yourself a writer?" he asked.

"I fancy myself a living creature, and living creatures must write to articulate their past and create their future."

"I am not interested in your philosophy. Tell me how the story ends," he said.

"We," she said, "you and I, even as we speak, are writing the ending. When you said that no one writes your life ..."

"Shall I open the flap?" Youngburton said, his fingers finding the seam in her neck.

"If that is how you wish the story to end," she said. "Then it shall be you and only you that remains in this room -- alone. Perhaps you will feel safer that way, but you will ask yourself what if ...?"

"I am not interested in what ifs, the make-believes of the world. I am only interested in what needs to be done now and how it needs to be done."

"You are not interested in the future?"

"The future shall take care of itself."

"So why do what has to be done now if you care not for the future?"

"I care less for your riddles than I care for your philosophy."

"Yet I can speak both in riddles and philosophy and still you appear to regard me as less than human? Why does the future scare you so?"

Youngburton began to feel cold. An icy chill crept through his bones. "The Empire is lost," he said.

"You knew that when you came here, you knew that before you met me, before you lay with me. But still ..."

"How does the story end -- 'The Man Who Should Have known Better' -- how does it end?" he asked again.

Eight

"So Youngburton is married," Dr Roberts said, sitting in a comfy wicker chair on Sarat Chandra Das's verandah and sniffing at the choti peg of whisky in his hand. "Who would have thought; I never took him for the marrying type. Still they say that Simla does that to people, something in the cool mountain air instils romance into the blood."

"I met his wife," Das said. "They passed through on their way to America. She is an exceptional woman; as exquisite as a porcelain doll, and her eyes, they have so much depth. When you look into her eyes you feel as if you are falling into the future."

"Like your naked fakir, Sarat?" Dr Roberts said, touching his lips to the whisky in his glass, just to get the merest taste of it. "He has eyes like that."

"Beyond my naked fakir," Das said. "I let her use my camera. She pointed it at the moon. This is the picture that she took."

Das walked along the verandah to where a recently framed photograph sat upon his wall. Dr Roberts sighed, rose from his chair nursing his whisky carefully.

"It is a man in a deep sea diver's suit," he said, squinting in an attempt to get the blurred background to move into focus. "A strange photograph for a young lady to conjure up."

"It is the first man on the moon," Das said. "He is wearing a moon suit. See the landscape in the background -- barren and grey -- filled with craters."

"Hmm, and is that an American flag?" Dr Roberts asked, jabbing a long surgeon's finger at the blurred flag that stood stiff and rigid next to the moon man.

"I believe it is," Das said. "I suppose you always imagined it would be a Union Jack?"

Dr Roberts remained silent, walked to the edge of the verandah, and looked up into the sky. The moon was half-full that night. There were things that he could not tell Das -- as he was sure that Das held secrets that he could not reveal -- secrets that were all part of the Great Game that they were engaged in. Dr Roberts knew enough to say no more.

But one creature built at great cost, so much time and effort, what would the Prince hope to achieve? Youngburton's words.

Oh I don't know, Dr Roberts found himself replying, as he gazed at the moon, perhaps the elimination of the most successful agent the Game has ever seen. He doubted Youngburton would return from America; he would be too busy chasing the future. Dr Roberts looked at his glass, raised it to his lips and drank the whisky down in one gulp. Sarat was right; he had imagined it would be a Union Jack.

To purchase this book, go to the How to Order page.

©2015 Go to top