Horror Fiction

INTERVIEWS

ARTICLES

Stephen King articles

BIBLIOGRAPHIES

Fontana's "Great Ghost Stories" Series

RELATED CONTENT

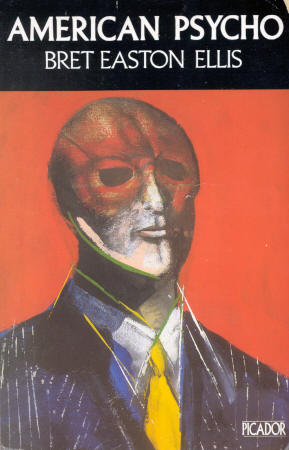

American Psycho

by Bret Easton Ellis, Picador. Reviewed by Sarah and Stephen Groenewegen

First Appeared in Burnt Toast#10, 1992

Much ink has been spilt concerning American Psycho. Here, in Australia, certain people in their 'wisdom' have declared it illegal for those under eighteen to purchase a copy. It is, according to these people, as dangerous to a person's health as alcohol or nicotine. The furore has been disturbing for a number of reasons, explored below.

Much ink has been spilt concerning American Psycho. Here, in Australia, certain people in their 'wisdom' have declared it illegal for those under eighteen to purchase a copy. It is, according to these people, as dangerous to a person's health as alcohol or nicotine. The furore has been disturbing for a number of reasons, explored below.

For a start, the controversy over-states the violence in the book. Parts of the novel are truly horrifying, but these only total about twenty pages. In a book of four hundred pages that is five per cent. However, and without going into market research, fewer people would have read it if there hadn't been such a fuss. It is literature in a style closer to that of Milan Kunders and Salman Rushdie than that of your standard crime fiction or horror novel.

Few, however, have been able to see beyond the violence. This is a strange perception because so much of it is so over the top as to be almost unreal. The exaggerated style used to describe the murders is an important feature designed to sicken the reader so there is less chance of empathising with Bateman (the psycho of the title) or being merely entertained by the book. Of course, it can be misinterpreted as glorifying torture and murder simply because it features so heavily. This argument is a specious one because the Bateman character knows his pathological need for violence is wrong and says so. He even goes so far as to confess all his crimes on the answering machine of a business associate.

Nor is the violence, in our view, particularly seductive. American Psycho is often cited in connection to Wade Frankum's killing spree as Strathfield Plaza in Sydney last year. The coroner's report noted the fact that he had a 'well-thumbed' copy in his possession. For some people this has been enough to condemn the book and justify its limited release. However, there can be no absolute proof that American Psycho was the cause of the murders, in the same way that it cannot be proved that heavy metal music is a significant cause of teenage suicide. Having a sole scapegoat (such as music, a book, a film) simply diverts attention from considering more tangible causes of such tragedies.

American Psycho has also been accused of being anti-woman pornography. Such arguments were also directed against Silence of the Lambs (see last issue's editorial). Jocelynne A. Scutt in The Bulletin (18/6/91) argues that any depiction of violence against woman is misogynistic. Unfortunately, such serial killings do occur, and to deny this would be an irresponsible delusion, obfuscating the real reasons and possible solutions. The use of graphic description serves a double purpose. Firstly, it reminds the audience that such horror occurs in real life. Secondly, these passages (and several of the scenes in Silence) act like short sharp jabs, which effectively convey the horror of each crime and its brutality. It is certainly not rousing violence, and in American Psycho Bateman's murders are committed out of compulsion. The book makes it clear that he does not gain any real gratification from the blood-shed, even though he seeks it. These bits are short, to the point, and never celebrated or glorified.

American Psycho is not just about violence, though, and as previously stated the latter only takes up a small proportion of the book. The major theme is the satirisation of the American dream, as twisted by the excesses of the 1980s. Bateman's habitat is the offices, restaurants and night clubs of Upper East side Manhattan. Yuppiedom is at its most extreme, and Ellis soon makes this clear with his presentation of characters and situations. People are described, not by physical characteristics or personality, but by the designer-label clothes they wear:

Dibble is wearing a subtly striped double-breasted wool suit by Canali Milano, a cotton shirt by Bill Blass, a mini-glen-plaid woven silk tie by Bill Blass Signature and he's holding a Missoni Uomo raincoat. He has a good-looking, expensive haircut and I stare at it, admiringly, while he starts humming along to the musak station. (p63)Most of these people take illegal drugs like cocaine, and are only really interested in conforming to their nouveau-rich lifestyles. Also included are continuous descriptions of nouvelle cuisine restaurant menus, audio systems, and television and video units, each with their expense high-lighted (not the descriptions of weaponry you might, perhaps, have expected). As Ellis notes, through Bateman, 'Surface, surface, surface was all that anyone found meaning in' (p375). It's a vacuous lifestyle that reflects the American Dream of equal opportunity and self-aggrandisement. This is a theme common to novels like F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby -- a critique of the focus on material over human values. American Psycho takes this to its extreme, and shows just how rotten to the core New York is. Politically, Bateman and his colleagues subscribe to the liberal capitalist ideal -- anyone prepared to work can make their fortune. He even lectures homeless people on their failure to 'achieve', or aspire to his hero Donald Trump.

Ellis is concerned not so much with spinning a tale as exploring society through the character of Patrick Bateman. Although the book deals with wider issues, they are seen through the eyes of its protagonist. Thus the book is written in the first person, which has surprisingly led to some confusion among critics. One of the most infuriating perceptions of authors is that they have experienced what they write about, therefore Ellis must be sick. American Psycho is not Ellis' autobiography! Bateman, though, is sick. He is a psychopath, suffers from hallucinations (which confuses the reader as to how many people he has actually killed), insecure ('I just want to be loved' (p345)) and has a 'severely impaired capacity to feel' (p 343). His illness is exacerbated by the combination of his social position and political ideas. This is reflected in Bateman's choice of victims: the homeless, prostitutes, blacks, homosexuals, and lower class people. His victims also come from his own social set, namely those he feels have betrayed him in some way.

Despite the compulsion to kill, Ellis is concerned that his readers should understand Bateman -- be interested, but not able to sympathise or condone his behaviour. Anthony Burgess adopted a similar technique with Alex in A Clockwork Orange. Ellis has achieved this by creating a character who is so misunderstood by those around him that he appears to have almost a double life. While the reader knows him as a psychopath, his associates view him as a harmless non-entity, 'the boy next door' (p11), and people constantly mistake him for others. This apparent double-life is somewhat similar to that of Laura Palmer from Twin Peaks, especially the juxtaposition between her reputation and real life, as revealed in The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer. Bateman is an even more complex character than the Laura Palmer reference suggests. Inferences concerning his personality can be drawn from many of the chapters, including one on his breakfast habits, another on his daily fitness program, and several that analyse his favourite pop groups (Genesis, Whitney Houston and Huey Lewis and the News). Such references indicate that Bateman has further interests than his more notorious activities suggest, and give him a much more rounded character.

While American Psycho has serious points to make it also has a fair proportion of humour (admittedly much of it black). The dialogue is often sharp and witty, and Bateman is an acute observer of the foibles of those around him. The pretentiousness of the characters is at times unbelievably funny, and this lightens the tone of the book.

We did not write this review simply because American Psycho has merit as a piece of literature. In fact, this review would not have been written, least of all in a Doctor Who/horror fanzine like Burnt Toast, except for the fuss that has surrounded the novel. We feel it necessary to defend it on the grounds that censorship is more dangerous to our culture than the book itself. Censorship is a denial of free choice. The decisions of those who censor can be based on subjective reasons, which can and do change over time. Over twenty-five years ago Nabokov's Lolita was deemed unsuitable for the Australian population because of its sexual premise. Today, its danger to our morals seems rather quaint. The further imposition that a censorship culture generates is an atmosphere where authors curtail their creativity. Literature is concerned with exploring the human condition, and this includes the darker side.

Editor's note

With a protesting letter less than three days after I posted BT#9 and the above refutation, I'm rather pleased with the effect last issue's Burnt Offerings has had. I stick by my words however, and their message that, although I am not in a position to comment on American Psycho's merit, it is well within my rights not to want to read it.

There is one final point that deserves to be made. Boyz N the Hood is an enjoyable and well-made film with a clear anti-violence message. At its American release there were riots among the LA street gangs it portrays, and the movie directly contributed to several murders. And nobody has suggested that such films be banned. Interesting, eh?

©2011 Go to top